Am I sobbing uncontrollably listening to Coldplay with my Sennheisers because I can’t go to the Coldplay concert in Vancouver tomorrow?

Yes. Yes I am.

Nope

We’re not going to the Coldplay concert.

Nate’s not feeling well, I’m super busy, and Covid.

And yes, I’m bitter about it.

That’s all I want to say.

Conflicted

What I want: to go to the Vancouver Coldplay concert in September

What I don’t want: Covid

What will probably be at the Vancouver Coldplay concert in September: Covid

Yes, I know I can wear a mask. And I definitely would if I end up going. But you need to understand something: I’m going to be at a Coldplay concert. All I’ll want to be doing is screaming and singing and crying, and none of those activities jive very well with wearing a mask.

Like…I REALLY want to go, but do I want to risk possible lifelong issues due to Covid for a two- or three-hour window of absolute bliss?

I don’t know.

MOVE OVER, SWIFTIES

CLAUDIA’S BUYING COLDPLAY TICKETS

I got up early to get my miles in so I could be in the ticket queue as early as possible. I’ve never bought tickets for anything like this before, so I was nervous about the process. But we got tickets!

I have no idea if the location will be ideal or not, but the floor tickets were already sold out once I got the option to pick (I don’t know if I’d do the floor anyway; I’m short and fighting my way to the very edge of the stage sounds stressful if they just let us all in at once), but I think based on how I’ve seen their show setup in other venues, this should be good.

WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

ZOMG

ZOMG ZOMG ZOMG COLDPLAY IS GOING TO BE IN VANCOUVER IN THE FALL

I NEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEED TO BE THERE

Tickets are on sale Friday. I’m going to be as close to the front of the virtual line as is possible.

I LOVE Coldplay. I have always wanted to see them in person. This is AWESOME.

Some Days I Really Miss Vancouver

Today, for whatever reason, is one of those days.

So here we go with random Google Streetview screencaps of Vanland, ‘cause I’m sad and my blog is as pathetic as I am.

My first place in Vancouver. It was a shithole. I wonder if it still has as many silverfish in it as it did when I was living there.

I visited this Superstore a lot during the summer of my thesis defense. It was a pain in the ass to walk to, but it was the closest Superstore to my apartment.

I walked across this bridge a lot.

PERSON, NO! You’re in the middle of Kingsway!

This park was the place I walked to on that one summer day in 2010 when I was feeling all claustrophobic in my apartment and had to get out and do something. It was only like half a mile from my apartment, but it was more than I had voluntarily walked in a long time (sad, I know). And it felt good. I mark this walk as my first walk walk and the thing that started all this current madness and obsession with walking.

Yay.

I Love Calgary

I really do. It’s a big enough city that you can get that big metro feel in certain parts of it, but it’s so spread out that there are a lot of places you can go and not feel like you’re in a big city at all.

And the river path. Holy gods, I love that river path. Miles and miles of uninterrupted walking with no threat of murderous cars? Give it here.

I love the weather, too, even though this past February made me want to throw myself into the sun (because at least then I’d be warm). I much prefer the temperature swings of Calgary (hot “near-90s” summers to cold “WHY ARE MY INSIDES FROZEN” winters) to the dreary rain of Vancouver.

I mean, I loved Vancouver too, but for totally different reasons and not with the same depth that I truly love Calgary.

(And I hated the rain. Ugh.)

A Thought

As you are all probably very well aware, I have moved around a lot in my life. Yes, most of that was in one city (Moscow), but I’ve moved a lot. Ask my mom.

At some point or another, I have missed living in most of the places I’ve called home, except for that first house on Grant St. (sorry mom) and that shithole I lived in in Vancouver for the first year or so (this one).

Another place that I’ve (surprisingly) not missed very often? My place in London, ON.

I miss the dorm room sometimes because it was so unlike a dorm room and more like a little apartment and I had it all decorated and pretty (this one), but I really don’t miss London at all.

I don’t know if that’s because those 70-ish days I spent there were part of a very bad time in my life or what, but I just didn’t enjoy it there. I knew I shouldn’t have gone, but I went anyway. And then had to come right back, haha.

That was really a rough time. Maybe I’ll tell you all more about it someday.

Maybe not.

Want to move to Van? Watch this.

Accurate.

I still miss it there every once and a while, though. My time at UBC was hell on earth, but the city was cool when it wasn’t trying to drown you in rain.

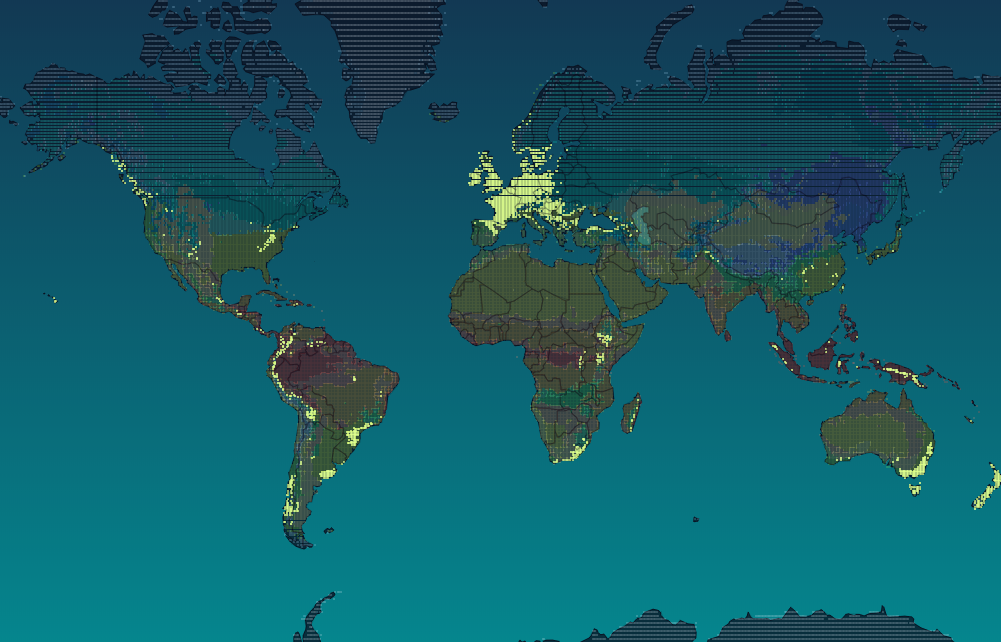

Are you Koppen with your climate?

So this is a cool little website. It lets you type in a city and highlights places around the world that have similar climates to that city.

Here’s Calgary, with its Dfb Koppen climate (continental climate, no dry season, warm summer)

Moscow, with its Csb Koppen (middle latitude climate, dry season in a warm summer)

Vancouver, with its Cfb Koppen (middle latitude climate, hell on earth no dry season, warm summer)

And Tucson, with its BSh Koppen (dry and hot semi-arid climate)

Nice!

TUANFUKFSD

Man, I just spent about an hour reading all my old emails between my UBC supervisor and myself.

I just logged on to that email to get info about an old account, why the hell did I decide reading all that crap was a good idea? I feel physically sick now.

Seriously. If I were to ever rank all the relationships I’ve ever had on a scale from “unhealthiest” to “healthiest,” that one would probably be the low point on the “unhealthiest” side.

That was not a fun time.

BRB, gonna throw up.

Some days I miss Vancouver.

And then I look at the weather there and think, “HAHA NOPE!”

Walkin’ on the Sun

Holy buttgoblins, I’ve been missing Vancouver today. I was actually going to blog about how much I missed the city (and walking around in it), but as I started doing so, I remembered something else that was related but more interesting than my usual Van blathering.

“What is it?” You ask, grateful that you don’t have to scroll past another “Claudia blah-blahs about Vancouver” post.

It’s Walk Score!

From their “About” page: “Walk Score’s mission is to promote walkable neighborhoods. Walkable neighborhoods are one of the simplest and best solutions for the environment, our health, and our economy.”

Basically, a city (or a specific house in a city, either way) is assigned a score depending on how “walkable” that particular city/house is. If a house is closer to major things like downtowns, restaurants, grocery stores, parks, etc., it will have a higher score. If it’s far away from such things. Or, in the case of a city, if there aren’t a lot of sidewalks or pedestrian-friendly routes, the city’s overall score decreases.

So let’s check it out!

Yeah, that looks about right. The blue dot is where I lived, by the way.

And this:

That looks about right, too. Calgary is fantastic at the inconsistent sidewalk thing. And the taxi drivers that want to mow down pedestrians. DON’T GET ME STARTED ON THE TAXI DRIVERS.

What about Moscow?

That’s…surprising, actually. I don’t know if it’s because there just aren’t that many grocery stores in the city or (because stores/restaurants/etc. seem to be pretty clustered in specific spots)? Moscow seems waaaaay more walkable than Calgary. But that might just be because I’ve walked it so many freaking times that a 3-mile walk to Walmart doesn’t seem bad at all.

Hahahaha, yeah. Yeah.

Sorry for the Crap Posts

Do-do-do-DOOOOOOOOOOOOO!

I can’t decide what to do about school!

So have a beautiful time lapse of a city I’ve already lived in, haha.

I like this better than the first one.

S-s-s-sad

Holy hot Jesus pitas, I miss Vancouver.

I’m abruptly falling apart; you interrupt me by breaking my heart

EEEEEEEEEEEEE REAL CANADIAN SUPERSTORE TIME!

But seriously.

It’s kind of overwhelming being back here. I remember the city pretty well and I really miss being here, but I have a lot of really screwed up memories of some really screwed up things that happened during my two-year stay here (remember this post?)

So yeah.

I’m excited to be here, but I’m also rather unexpectedly sad.

Which is making it hard to go out and walk the city.

WHICH IS MAKING ME EVEN MORE SAD.

GUESS WHERE I AM

HERE ARE SOME PICTURE HINTS

Any guesses?

VANCOUVER!

My mom and I drove to the Seattle-Vancouver border crossing so that I could get my study permit for fall. We were under the impression that you could only get those at the large (or at least moderately-sized) crossings, not dinky ones like the one in Idaho.

But apparently you can, according to one of the border guard dudes.

So darn, I guess this fun little jaunt to Vancouver was unnecessary.

Darn.

(Not sure if the sarcasm is getting across here. I’m being sarcastic, y’all.)

Internettin’

Haha, oh, Sound Cloud.

Do you remember this? DO YOU REMEMBER THE NIGHTMARES?!

I saw this video quite a few years ago and now this song always reminds me of Vancouver:

Another awesome Rage Quit I don’t think I’ve ever posted on here.

Well.

This is probably as personal as you’ll see me get on a public blog post. I was hesitant about even posting this, but I really needed to write it, and so I think it should be read (or readable; I don’t really expect anyone to take the time to peruse this drivel).

Disclaimers (‘cause everything I do has at least one disclaimer):

- I feel like the guy who wrote A Million Little Pieces by saying this, but this is what I’d like to call semi-fictional.

- The non-fiction parts: everything in here is 100% true as far as the feelings/thoughts go. That part is very honest and as accurate as I could portray it with words. Everything that happens action-wise is also true. I walked where I said I walked, I went to the hospital, we had the earthquake drill, etc.

- What’s FICTION is the fact that—well, I omitted quite a lot, and the stuff I DID include I rearranged a bit to make it more “story-like” (and able to fit in 25 double-spaced pages). The hospitalization I write about actually occurred in April. I didn’t go to Richmond until like March. Counseling started back in September of 2010.

- And probably the biggest fiction: “depression” is code here for “all that shit that made life suck up there for me.” If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you likely know what that all entails, so I won’t reiterate it here for you. But either way, that’s why the “chronic depression” line had to be woven through there. So when you see “depression,” you know what that means in the context of this story. So ignore that whole thread if you know what I’m really talking about.

- One last note: this is the “abridged” version of this story. The longer version is at about 60 pages and shows no signs of completion, but I think this length works for what I’ve got here.

Anyway. Here it is.

~~

If you hold out your right hand so that your palm is facing you, your fingers are pointing to the left, and your thumb is held away from the rest of your hand in at a slightly crooked angle, you get the general idea of the shape of the city of Vancouver, British Columbia. The fingers of the city point west across the Strait of Georgia and towards Vancouver Island, which acts as a buffer between the harsh waves of the Pacific Ocean and the inland metropolitan area home to just a little over 2.3 million people.

In August 2009, I was headed to the tips of these fingers to attend graduate school at the University of British Columbia. Before loading my things into a moving van and driving across the state of Washington to head up through Seattle, Canada had always seemed like a distant and unreachable place—somewhere I would never go, despite my home town sitting a mere 250 miles south of Alberta. But handing my study permit to the border guard and getting my passport stamped for what would be the first of many times, the fact that I would actually be attending school in a foreign country had finally become my reality.

Vancouver sits almost due north of Seattle, but to get there you have to drive in a curve around Puget Sound and all of its encroaching smaller inlets and bays before reaching the US-Canadian border. Once you’re granted a passing inspection by the guards, it’s a mere 30 miles (or 48.2 kilometers) to Canada’s largest western city and eighth largest city overall.

I was intimidated upon my first arrival in Vancouver. I liked big cities but I had an acute fear of getting lost in one. Thus, my first year of graduate school was spent almost exclusively in the safety of the single bus route that would take me from my apartment to campus and back and in the block around my apartment building.

That first year I had no need to go anywhere other than school and home, nor did I want to. At that point, all I had wanted to do was to have left my small hometown of Moscow, ID and live, for the first time, in a place that wasn’t bordered by wheat fields and wasn’t the subject of many a worn-out potato joke. Being away from my parents and away from everyone I’d ever known afforded me the opportunity of a completely new beginning. This was what I had been counting on: a chance to start over.

What I hadn’t been counting on was the depression. Looking back, though, I’m not sure why I hadn’t seen it coming. My depression is clinical but not chronic. Simply put, it means that it’s severe enough to warrant a diagnosis but doesn’t stick around long enough for any one stretch of time to be considered a prolonged condition.

Every several years I suffer a lapse, falling away from normalcy and into a sort of mental fog that makes every day functioning akin to trying to run in quicksand. As my phenomenal luck would have it, one of these lapses happened to coincide almost exactly with my move to Vancouver and the start of my graduate program.

I managed to make it through the first year with little incident, still maintaining my grades and making appropriate progress on my thesis. But by my second academic year I could feel things starting to truly slide out of my control, and by fall of 2010 I felt unable to continue at my current state of functioning.

For many people suffering from depression, the illness acts almost like a sedative, dragging them into a dream-like state of inactivity and making it difficult to even build up the motivation needed to leave the house. My depression always countered this nearly universal experience—rather than the common feelings of listlessness and lethargy, my depressive periods were marked with an almost irresistible urge to get up and move.

The many doctors I’d seen over the years had a name for this inner restlessness—akathisia—and many of the doctors “reassured” me that sometimes such a thing developed spontaneously and that I shouldn’t be worried about it.

This reassurance did little for me during the early fall of 2010 as I spent my time outside of school rearranging my apartment, cleaning every corner and hard to reach light fixture, and even helping my neighbor in the apartment across the hall clean out her storage unit in the garage—anything to try and cure the restlessness. The stereotypical coping method for dealing with depression—curling up on the couch and forgetting the world outside existed—was something that would not work for me; I would have to figure out something else. Escaping mentally was proving impossible. I would have to escape physically.

~

My first legitimate outdoor adventure was due to a particularly beautiful Sunday in late October. I was restless as usual, but found myself unable to quell it with any indoor activity. Thus, inspired by the weather, I donned my shoes and jacket and headed out into the rare sunlight.

Vancouver is segmented into 23 “official” smaller neighborhoods. Some are distinguished by geography, others by history or by some demarcation in the transit system, and others exist due to the clustering of certain cultures. My neighborhood was of the latter type. Victoria-Fraserview, one of the most culturally diverse neighborhoods of Vancouver, exists as a segment of the city containing several tight clusters of Middle-Eastern and Indian groups. It sits near the southeast corner of Vancouver, on the fleshy part of the lower palm.

My apartment was located on the northern fringe of a large Arab community that spanned several blocks. I lived along Fraser Street, a major north-south road that was heavy with specialty shops and an overabundance of pizza places. The street was always busy. During the day the shops would open and men and women the color of sandpaper would drag their wares onto the already crowded sidewalks. I would always pass the busy shops on my way to the bus to campus, but never had I stopped and shopped.

But my very first walk that October day had me southbound, headed down Fraser Street. Even in on Sunday the neighborhood buzzed loudly with activity in the sort of controlled chaos that I assumed was second nature to the people of a large city.

As I made my way south I took my first real glance at the interactions around me. Fluttering hijabs, displayed for quick sale, chased the shoulders of those who passed by too rapidly to give them a glance. Sidewalk-parked carts of bruised produce and unpronounceable spices created bottlenecks of foot traffic along the narrow sidewalks, large families orbiting the carts in search of the best wares.

That first day I made it to the next major intersection ten blocks south—approximately half a mile out from my apartment—before turning back. My fears of getting lost in a big city were warranted as I had never been too good at orienting myself in an unfamiliar place, and like a novice swimmer taking their first dip in the ocean, I was cautious about being dragged too far out and not being able to find my way back.

Upon returning home, I realized that though I hadn’t been gone for longer than half an hour and failed to even leave my neighborhood, I had, in fact, cured the restlessness that had been plaguing me all weekend. And as the Sunday sun began to dip behind an encroaching wall of grey clouds, I felt a momentary calmness that I had been lacking for months, ever since the depression had decided to make its pilgrimage back into my mind.

~

Europeans first explored the area of present-day Vancouver in the late 1700s, the first of them being the British naval captain George Vancouver. The Strait of Georgia brought Vancouver and other initial explorers through the area in their quest to find a water route leading to inland Canada. Fur trading led to the first thorough exploration in 1808, and the Fraser Gold Rush of 1858 brought nearly 25,000 men through what would later become Vancouver’s downtown as they made their way to nearby New Westminster.

However, it wasn’t until 1863 that a newly constructed saw mill led to the first settlement of the area. The mill was the sole source of income for the entire population of the budding community until the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s, which brought with it a boom in both economy and population. This original settlement, called Gastown after John “Gassy Jack” Deighton, owner of the tavern established next to the sawmill, then began to grow and spread outward. Today, Gastown marks the center of Vancouver’s downtown.

It would be awhile before I myself would spread outward beyond my immediate surroundings and walk through historic Gastown. For the first few months of walking, at least through December of 2010, I preferred to stay in a relatively limited radius around my apartment and would usually only walk in a linear direction before making my return trip back home.

At the beginning of November I purchased a pedometer and started tracking the statistics of my walks. At first I just tracked the distance, but soon I began writing down every number the pedometer reported about my excursions: distance, date, duration, and number of steps. It didn’t take long for me to fall into a pattern. I would take relatively short walks during the week (few longer than my first outdoor adventure) and spend my Saturday walking somewhere I’d never been before, leaving around noon and not returning until 5 or 6 that evening.

Many of these first walks were to destinations to the east—usually shopping malls since they were the easiest to pinpoint when planning my routes and were often along major roads (I was still in fear of getting lost). I would usually plan so that I would hit my designated mileage goal by the time I reached my destination and then would return via public transit in order to beat the veil of twilight that would shroud the still unfamiliar streets in darkness.

I began to develop a sort of absent thought on my walks as the year came to a close. I’m the type of person who struggles with raw observation, as it’s hard for me to focus on one thing without also being preoccupied with something else. Even when watching television I can only truly justify it if I’m doing or thinking about at least one other thing along with it.

This is true in other aspects of my life as well. Many times I’ve passed within an inch of a good friend as we walk by each other on the sidewalk without even so much as noticing them, my mind occupied by something else that had occurred during the day or with plans for something that’s due to occur later. There is always the interference of anticipation clouding my focus, regardless of what that focus is.

The majority of walks I took at the end of 2010 were plagued with this sense of distracted observation. I could sense the city around me, I knew where I was walking and the landmarks I passed, but it was if I was simply moving through it. I had trouble focusing on the details of where I was. The city was leaving no mark on me and I was leaving no mark on the city—we were two different entities separated by a lack of observation.

But the further out I began walking, the more I found my mind cleared of the static of this distraction and the more time I spent taking in parts of my surroundings, pondering them, and then releasing them easily from my mind. It wasn’t long before I found myself doing this with the worries that continually bombarded the otherwise peaceful walks. It was as if my motion within the city allowed me to discard the excess buildup of worry and discontentment.

Sometimes I would find myself so caught up in this absent way of thinking that I would actually surpass my intended destination and would be walking into unknown parts of the city as darkness inked the sky behind me. Depending on where I was, I’d either have to make my way to a familiar-looking bus route or, if I were near a station, would take the much faster method that was the SkyTrain and be dropped off by the mall a half a mile from my apartment.

~

When you think of the stereotypical metropolis of the future, you probably picture its public transportation as something along the lines of a rapid, monorail-like system, twisting its way through the city in a completely automated fashion to avoid the risk of human error.

The Vancouver SkyTrain is this fantasy brought to life. Initially constructed to handle the increased population of the city as it hosted Expo ’86, the track debuted the summer before, in 1985. The original route runs diagonally through the city, following the lifeline, from Waterfront at its northwestern-most stop in downtown, to the King George station in southeast Surrey, dipping below ground for most of its journey and surfacing at either of the endpoints.

The success of this rapid transit system led to further expansions. The original route was renamed the Expo Line upon the addition of the Millennium Line track in 2002 and the Canada Line, which runs north-south from downtown Vancouver to Richmond and was opened a mere two days before my arrival in the city in August of 2009.

The SkyTrain (now the name for the whole network) is completely automated with trains arriving nearly once every two minutes at most stations. Built to match the rapidity of everyday metropolitan life, the trains travel at highway speeds of 80-90 kilometers per hour and, when above ground, allow passengers a unique, almost tourist-like experience of the city. The system almost begs for a pre-recorded guide announcing the landmarks and prominent shopping malls as the train speeds above the trees and buildings.

There is nowhere in the city where you can witness the transformation from wealth to poverty that occurs as you move from West Vancouver to East better than on the SkyTrain. I frequented the Millennium Line the most. It is unique among the three in that it travels in a loop to return to its main station rather than having to switch direction on the same track and travel in reverse, retracing its path. Thus, if you follow the Millennium Line all the way back around to the stop at which you boarded, you find yourself looping into (or out of) East Vancouver.

The station closest to my apartment was one of the westernmost stations on the line, but I was usually well into eastern Vancouver when, after walking for most of the day, I would decide to use the SkyTrain as my preferred method of getting back home.

At a walking at a pace of about four miles per hour, I missed the subtle transformation into poverty that occurred between my own apartment and my usual easternmost destinations. But riding the SkyTrain on my way back home, I would always watch the old, graffiti-tattooed apartment buildings give way to industry and commercial lots—the shopping streets of middle Vancouver—which would then slowly dissolve into neighborhoods with more trees, larger houses and nicer streets. Eventually, I would again see the lush lawns of the multi-million-dollar houses that populated much of Vancouver’s West.

The SkyTrain was usually a western Vancouverite’s only way to glimpse the poverty that stained the eastern rim of the city. The only way westerns on the Millennium Line could possibly remain ignorant to the change in wealth would to be to keep their eyes focused forward and not look out the windows where poverty rushed away from them at a comfortable, speedy pace.

~

Depression impoverishes the mind. It takes money you don’t have to pay dues you don’t owe, and fabricates new dues any time you start to regain your footing. You find yourself constantly assessing your mental accounts—do you have enough energy for this? Can you handle such-and-such without falling further into debt? And while you can look away from it and pretend it’s not there, even in your most mundane daily activities you feel it pressing on you, a constant stressor on your normal functioning and relationships.

By the end of December I had fallen far into this mental debt. As the depression further saturated my mind, dragging it down to a level of functioning where planning, anticipation, and expectation were things too difficult to manage, I was somehow able to retain my Saturday walks as a source of something stable that was outside my own self. Some weekends they were my only reason for getting out of bed. If I can walk just two kilometers today, I would tell myself as I lay curled beneath the covers, I will have succeeded. It’s all I need to do.

At the beginning of 2011, my doctor on campus, aware of my struggles, recommended that I go see a counselor. It was something I had neglected doing both because I was unsure as to how Canadian health care actually worked (and if I would be covered as a foreign student) and because the effort of finding out required a level of caring that had long since faded out of sight under the haze of the depression.

Sensing my lack of willingness, he set up the first appointment for me, and in mid-January, I found myself heading to an area near downtown Vancouver that I had yet to explore to visit a counselor who specialized in clinical depression.

The bus stop for the route I needed to get to the counseling office was less than a block away from my apartment. I stood there for the first time on a Monday morning, the threat of rain hovering over the city. By the time I’d reached the office, the rain had followed through with its threat and was falling in heavy sheets that lapped at the buildings and streets in the strong wind.

My first meeting with the counselor was an hour long and involved all the mundane questions of a first session—background, previous therapy, previous medications, and a discussion about what brought me to counseling this time around.

Before leaving, I had set up weekly appointments that would fall on early Monday mornings before my afternoon classes at school. As I stood in the lobby with my counselor as she filled out an appointment card for our next visit, the wind outside whistled through the old surrounding buildings and the rain spattered in a staccato beat against the large glass windows.

“It seems to rain down here more than it does at my apartment,” I commented.

My counselor laughed. “I wouldn’t be surprised at that.”

~

Vancouver’s climate is so well-known for its rainy disposition that it may come as a surprise to discover that the summer months—July and August, mainly—often result in mild drought conditions due to a lack of precipitation. Summer rainfall rarely tops 40 millimeters per month—less rain than the average summer rainfalls of Houston, Miami, and Hartford, among other US cities. But for the rest of the year, Vancouver lives up to its reputation as “Canada’s Seattle” due to its wet winters dumping an upwards of 180 millimeters of rain per month.

In a typical year, nearly 1,200 millimeters of water cascade from the sky onto the city below. If it were all to fall at once, Vancouver would find itself in an instant under nearly four feet of rain. Luckily, the large volume of water is more reasonably dispensed, with some form of precipitation falling on about half of the days out of the year.

I consider myself extremely lucky, given the number of hours I spent walking, that relatively few of those hours involved walking in the rain. Be it a blessing from the gods of meteorology or just my beating the odds, only one of my many long Saturday walks was undertaken beneath actively precipitating clouds.

In the winter months I often found myself either walking in the aftermath of such storms—the cement sidewalk blocks, broken and distorted by underlying roots, holding pools of freshly-fallen rainwater—or in the calmness before them. If the storms were approaching, the clouds seem to droop to the ground with the weight of their contents and the whole sky obtained a menacing, anticipatory grey before unleashing hours of unrelenting precipitation. In such times I was usually able to make it home mere minutes before the downpour.

While I was usually without rain on my walks, it didn’t necessarily mean I had the companionship of the sun. I found Vancouver’s persistent cloud cover more of a distinguishing feature than her rain. The sky was almost perpetually gray; this grayness seemed to bleed down into the city itself, as if someone had painted watercolor clouds above the cityscape and then had held the painting vertical before the clouds had time to dry, the watery grayness mixing with the colors below, muddying them into a general haze. What’s more, the clouds themselves seemed to hang incredibly low in the atmosphere, making it seem as if the skyscrapers downtown were literally scooping their way through the grayness that surrounded them.

I had never experienced an atmosphere so low. In my hometown, clouds had stayed where they were supposed to—above the land, above the cities—and there was legitimacy in the phrase “rainfall.” In Vancouver it was almost like the city was living within a cloud itself, and as an interloper to this part of the water cycle, it was expected that the city and its residents anticipate the rain and tolerate the world of grayness.

Sunlight itself was a rare commodity. Days of blue skies and sharp shadows were like rare feasts in a time of famine. One of these rare sunny days occurred on a Saturday in February. Taking advantage of the weather, I walked to Richmond—my first walk that took me outside Vancouver’s borders and into its neighboring southern city. Richmond was exactly 13 kilometers from my apartment on the route I took—18 minutes by car at highway speeds.

To reach Richmond from Vancouver you have to cross one of the outwardly threading fingers of the Fraser River, the geographical boundary between the two cities. Richmond sits at an average elevation of one meter above sea level and thus is especially prone to flooding. Lucky for the city, it receives about 30% less precipitation than its larger neighboring city to the north—though that day it didn’t matter, as the surplus sun knew no boundary between cities and thus shone its golden warmth down on both of them.

Still, though, I could tell it had recently rained in Richmond. The city is located in the Fraser River delta and rests largely atop alluvium soil: loose, unconsolidated particulate that sits in soft sloping deposits shaped by nearby water—in this case, the tributaries of the Fraser River. When saturated with rain, the fertile soil surrounding the city takes on a deep brown-red hue, much like mahogany. It was this color that I could see as I crossed the Oak Street Bridge into the city proper.

Alluvium soil is “young” when viewed on the scale of the geological timeline. Most is no older than 2.5 million years. A similar sense of youthfulness is also reflected in the city of Richmond itself, which was constructed only in 1879—thus making the joint feature of this particular city poised on this particular type of sediment a rather new mark on the face of the earth.

~

The North American Tectonic Plate is the technical term for the large sheet of earth’s lithosphere that houses the land masses of North America and Greenland. The western lip of this continental plate meets another plate (the Juan de Fuca) about 250 miles off the coast of Western North America. This smaller oceanic plate is currently subducting, or moving beneath, the North American Plate, being forced into the mantle below at a steady rate of about .11 millimeters per day, shortening the width of the Pacific Ocean by about a thumb’s length each year.

The meeting place of these two plates is known as the Cascadia subduction zone and is the source of the seismic and volcanic activity that dot the Pacific coast of North America from Northern California to the southern coast of Alaska. It was the heat generated by the slow dance of these massive plates that was responsible for the eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington in 1980 and the blast that created Crater Lake in Oregon nearly 7,700 years ago.

The active area of the subduction zone extends about 200 miles in either direction of the fault line itself. On the inland side, every town and city within the zone is considered to be “at risk” for severe damage should a significant disturbance ever occur at the fault line.

With nearly half of its province sitting within the active zone, British Columbia officials instituted a series of province-wide earthquake drills in 2011. The first, humorously titled the Great British Columbian ShakeOut, occurred in early January of that year and was taken seriously only in the smaller towns that had nothing else to do with their time. Vancouver did not participate, the city government claiming that such a drill would interrupt the flow of businesses going about their workday routines.

It took the magnitude 9.0 earthquake that struck Japan two months later in March (and also put Vancouver Island on tsunami alert) to force the city to reconsider the necessity of the drills. Vancouver not only sits within the boundaries of the subduction zone but was constructed partially over the same alluvium that underlies Richmond. Due to its loose nature, this particular sediment would virtually liquefy in the event of any significant seismic activity, giving way beneath the city and causing more devastation than would occur with a more stable ground type. Thus, Vancouver sits like a house of cards atop an unsteady table. One bump and the world topples. Upon reconsideration of these facts, the city decided in favor of quake preparedness.

I had been in a counseling session when the first citywide drill occurred at the end of March. While the standard earthquake procedure I had been taught was to take cover under a stable table or desk, we had been instructed to file calmly out into the street when the downtown sirens were sounded. It was almost like a fire drill.

My counselor and I had been discussing the possibility of medication before the drill. She was insistent that I was at the point where I could no longer continue at my current functionality and needed pharmaceutical help in doing so. I was adamantly opposed to this, having tried medications in the past and each time coming away with adverse side effects that far outweighed any possible benefits.

We originally tried to continue our discussion as we stood outside, huddled against the building to stay out of the rain, but in the end we fell away from the subject and spent the time mundanely discussing the weather with the office secretary.

The earthquake drill cut a large time out of my session hour; when we were eventually permitted back in the building it was time for me to leave and head to campus. My counselor knew that school was becoming a struggle for me. After we’d finish our sessions she’d always ask me if I thought I was stable enough to go into campus that day. And every time I said “yes”—which was always—she seemed to doubt my resolution.

“I know school is triggering,” she would say. “I don’t want something to happen that will cause you to go somewhere mentally that you can’t get out of.”

I always reassured her that I would be fine. In my years of dealing with depression, I had never been so imbrued with hopelessness that I lost all motivation to go to school. So each time I convinced her that I was, in fact, okay to return to my usual activities.

This time was no different. She asked if I was okay to go. Despite my longing to just return home, I assured her that I would be fine to return. But each time she asked, this time included, I found myself questioning my conviction a little bit more. I hadn’t yet reached a level of depression that would cause me to lose my daily functioning…did that mean that it would never happen? Or would an incident eventually occur that would cause the depression to become so overwhelming that I couldn’t break free?

With each of my counselor’s doubts my own began to grow, and I began to wonder a little bit more if I wasn’t, in fact, prepared for the worst—whatever that may be. And while I had convinced myself that I was stable, this conviction alone was hardly reliable ground to stand upon. There was nothing to prevent something coming along and bumping this stability right out from under me and cause my world to fall apart. I, too, was like a house of cards.

~

My counselor’s office was located in the Hastings-Sunrise neighborhood, one of Vancouver’s largest and one that shares a border with the eastern city of Burnaby. On your open-palmed hand, Hastings-Sunrise would occupy about a square inch of the soft pad beneath the thumb. It was the furthest east you could be while still being within city boundaries.

The core of Hastings-Sunrise is Hastings Street itself, which skirts along the upper rim of the palm just below the thumb. The street divides into West Hastings and East Hastings at about the midpoint of the city. Head towards West Hastings and you eventually reach downtown. Head towards East Hastings and you traverse the northernmost edge of the city before reaching Burnaby.

East Hastings is a district of homelessness and drugs. Large houses give way to concrete buildings and commercial lots; kempt sidewalks deteriorate into broken and pitted slabs; corners are populated not with the decorative shrubbery found on downtown intersections but instead with homeless men with complexions of dirt and desperation, holding worn out hats to anyone willing to part with some change.

As often as I frequented these urban badlands, I was never accosted. Either I was not a particularly appealing target for desperate meth addicts and the homeless, or even the strung out, alcoholic Vancouverites of East Hastings fall into the typical American-held stereotype of the “Perpetually Nice Canadian” and leave innocuous, fast-walking girls and their iPods alone.

Hastings Street was about five miles from my apartment and, once the weather started improving in April, served as a common branching-off point for many of my longer walks. By this time I had accumulated a total distance of nearly 1,200 kilometers, or about 760 miles: the equivalent distance of walking from Seattle to Sacramento.

I was no longer afraid of deviating from a linear route. A consequence of getting to know the city at such an intimate level was the expansion of my mental map. For my first year in Vancouver I could have placed a sheet of butcher paper over a map of the city and cut away only a small bit of the obscuring paper, revealing a small radius of map around my apartment and the single bus route that took me into campus. What was exposed was all I knew of the city.

But by April, the portion of the map that was revealed to me far exceeded the amount of butcher paper remaining, and the further I went, the closer I was to removing the paper entirely. Walking Vancouver’s many streets was like making friends with the roads and architecture, the parks and grocery stores, the street lights and stop signs—I was getting to know the intimate parts of the city better.

The more familiar I became with these minute bits of Vancouver, the less lost I felt, even on my longest walks that took me to her fringe neighborhoods and bordering municipalities. Every turn into the unknown revealed a previously unforeseen connection to some other familiar street or bus route that could lead me back when the time came to turn around and head home from my excursion away from reality.

~

If you travel north of Hastings Street—up from the pad beneath the thumb to the thumb itself—you reach Vancouver’s downtown. Here is where you feel her pulse the strongest. Over two dozen major streets meet and spiral together, creating a single-chambered heart that pumps life in and out of downtown, to and from the extremities of the city.

The heart of Vancouver itself is an amalgamation of old and new: skyscrapers built in the last 50 years point like the heads of needles out of the pin cushion of older architecture sitting stories below. The mixture of the two is what gives downtown Vancouver its distinctive flavor of modernity mixed with custom—a city molting its old skin while still retaining the same body beneath.

Douglas Coupland, a Canadian author who spent a stint in one of the city’s steel-and-glass high-rises, made a study of the unusual architecture in a collection of essays entitled The City of Glass (which eventually became the city’s newest nickname). In the essay bearing the same name, Coupland notes that these crystal-like stalagmites are what give Vancouver a unique downtown profile amongst all of Canada’s major metropolises.

The glass used in many of downtown Vancouver’s high-rises is of a striking sea foam color and is accented with supports made of similarly-colored steel. It’s almost as if tidal waves had crashed into the low-lying downtown area and formed the massive structures, leaving their whitecaps frozen at their pinnacles, remaining in place as pillars of glassy sea that shock the eye when viewed against the din of the older, shorter architecture.

I loved downtown. I loved being amongst the glossy green buildings. Each time I went I risked the panic of getting lost (downtown remained the one area of the city where, even after many walks, I wasn’t yet comfortable navigating without a map), but each time I found myself there I felt an odd sense of pending resolution when it came to my depression.

Being downtown made me feel like I was part of some greater organism. It was a comforting feeling to know that I was encapsulated within the greater system of the city, something that would live and thrive and grow independently of any single individual within it. The onus of carrying on as a functional adult was lessened when I was in the heart of Vancouver, knowing that the “something greater” was still thriving even while I myself was not. The whole world will not fall apart without you, it seemed to say with its rushed chaos and cacophony of a dozen clashing cultures. The world is not a machine that depends on every single cog to be working every single moment. Things will be okay, even if you aren’t right now.

Leaving downtown would leave me with a nascent seed of hope. I would get over the depressive episode and resume my normal place with my normal thoughts and normal emotions. Maybe not that day, maybe not the next, maybe not in two months’ time. But I would, on my own, thrive again.

~

If downtown acts as the heart of Vancouver’s human activity, it acts as her lungs when it comes to her climate. Vancouver’s unique geographic location affords the city a series of microclimates—dramatically different weather patterns affecting different parts of the city due solely to local geography. Her downtown is particularly afflicted by sea breezes. The great city seems to inhale and exhale with the coming and going of the day, these gaping breaths lasting for hours on end as sea and land seek equilibrium in air pressure and temperature.

Gusts of wind would be drawn up into her glass bosom as morning came, crashing against the tall buildings not unlike an incoming wave crashes against coastal rocks. These same winds would be exhaled at night, the cooled city air flowing back out to sea, downtown temperatures dropping at least 3-4 degrees Celsius as the sun sank and the night came.

The further north you go—past the upper border of Vancouver and into the independent city of North Vancouver—the windier and cooler it gets. One of my favorite destinations that took me through the heart of downtown and into the northern city was the Park Royal Shopping Centre. It was nearly 17 kilometers from my apartment if I took my preferred route and thus was a good way to rack up weekend distance. I would walk west a bit, head north into downtown, and then follow the arc of highway as it bent through Stanley Park—the very tip of the thumb—before heading into North Vancouver.

Stanley Park is nearly 10% bigger than New York’s Central Park and is bisected by the highway that links North Vancouver with Vancouver proper. Walking through the park alongside this highway was enjoyable regardless of the weather; the ancient trees that thrust their drooping, century-old branches into the sky provided a canopy of foliage that significantly reduced the amount of rain that made it to the ground below and shaded those beneath on those rare sunny days.

In addition to walking the 2.4 kilometers through Stanley Park, getting to Park Royal required crossing two bridges—one of the three that led into downtown Vancouver, and then the longer and higher Lions Gate Bridge on the way out of Stanley Park.

The Lions Gate Bridge gets its name from the two mountain peaks that sit north of Vancouver. The bridge’s design pays homage to this name with a two pairs of car-size stone lions that sit like guardians at either entrance. The bridge is almost two kilometers across, spanning the Burrard Inlet that separates North Vancouver from Vancouver, and the road that runs across it has a vertical clearance above the Inlet of a little more than the length of half a football field.

If you were to fall from the bridge at its highest vertical rise, you would hit the water below at a speed equivalent to the cars passing horizontally above. It would almost certainly be a fatal plunge. It is this fact and the lack of any barriers higher than shoulder-height that make the bridge a magnet for the suicidal. Between 1997 and 2007, 45 people successfully ended their lives by leaping from the bridge’s walkways, the second-highest suicide count for any location in Canada during the same span of time.

In lieu of constructing expensive suicide barriers, the city of Vancouver opted for the installation of a series of emergency phones placed in increments along the bridge’s walkways. These phones connect directly with emergency services if picked up, and are designed as last minute life-savers should either a jumper change their mind or an observant citizen take the responsibility to step in.

It’s hard not to notice these phones from the walkway along the side of the bridge. They stand out in their fluorescent yellow against the subdued red of the painted girders. I often wondered as I walked past them if they had ever been successfully used, or if most suicide attempts took place late at night or very early in the morning, when traffic on the bridge was at a minimum and there was less chance of a driver or passenger glancing to the side and noticing a desperate figure climb onto the ledge with intentions to disappear into the evening-born fog bank below.

I wondered about the level of desperation needed to turn one’s mind towards suicide. Be the cause from stress, depression, or loneliness, I figured that everyone had a tipping point somewhere in their minds.

Despite the depression that was steadily getting worse in my own mind as April turned into May and May into June, I myself had no contingency plan of ending my life via the Lions Gate Bridge or any other method. But at the same time, I was no stranger to that feeling of in-the-minute raw desperation. When the mind is clouded by the dust of everything around it collapsing, what does it turn to in order to restore clarity?

~

In early June, about two weeks before I was scheduled to defend my thesis, I was hospitalized. The days were especially long by that point thanks to Vancouver’s high latitude, with summer’s daylight hours lasting from about 5 AM to about 9:30 PM.

But the nights were exceedingly dark, the moon and constellations above blotted out by the clouds that would creep their way across the horizon by nightfall. On one such night I found myself in a moment of that raw desperation. Like a storm that feeds on a smaller weather system, the depression had been slowly consuming all my anxiety about my defense and had grown into something that no longer loomed above my thoughts and reasoning but instead began to drown them in a downpour of irrational panic.

Feeling like I was out of options and trapped in the present with no clear vision of any sort of manageable future, I made the decision to call the crisis line my counselor had given me months earlier. I told them of the situation and they insisted on sending an ambulance to take me to the hospital.

I had thought I sounded calm on the phone, but there must have been something in my voice because when I opened the door to their knocking I found they’d sent two paramedics and a policeman to come get me. After brief questioning to assess that I was only a danger to myself and not to others, they escorted me quietly to the ambulance that was waiting out front.

Vancouver General, Canada’s second-largest hospital, sits on the edge of downtown in a cluster of large buildings I had walked by on many occasions. The hospital receives 75,500 people per year—that’s about 208 people per day—through its emergency room doors. Many of these patients are returned to the city almost immediately after needing only minor repairs or a quick dose of medicine. The rest are swallowed for an indeterminable amount of time by the hospital’s gaping wings before seeing daylight again. Some of them never leave.

3 AM is a common time for a specific breed of patient to arrive at the hospital’s doors. Most are residue from the city’s nighttime activity: tough guys with busted lips and lacerations from drunken fights, inebriated homeless who have spent the days’ earnings on evening alcoholic binges, the poorest poor from East Vancouver and Surrey coming to the hospital only after their illnesses have made them virtually unable to function.

Then there were people like me. I was kept in the emergency room’s small east corridor, which was exclusively for psychiatric cases. Upon my arrival to this wing, my walking shoes, worn almost all the way through by that point, were put into a bag along with the rest of my clothes as a nurse ushered me into a hospital gown and then into a bed.

I was left alone for much of the remaining night, apart from a nurse offering me a blueberry muffin from the breakfast cart once the sun rose and from the hospital’s psychiatrist around 8 in the morning. He asked me the standard questions, including if I’d ever made a specific plan for a suicide attempt. This I responded to with an earnest “no,” deciding not to mention anything about my ponderings of Lions Gate Bridge.

My assessment apparently raised no flags, and since I had come voluntarily, I was told that I could leave if I felt I was no longer a threat to myself. In my apartment the night previous, I had felt an overwhelming hopelessness that was amplified by my being alone. The familiarity of my surroundings had felt suffocating and constricting—a place of no escape. I told them this as they checked me out of the hospital, adding that I’d just needed somewhere safe to be for the night—a place away from the familiar—a place where I could be with other people rather than just with my own thoughts. I’d just needed a little distance.

~

In the few weeks that remained between the night of my hospitalization and the defense date of my thesis, I walked very little. My shoes sat neglected in the closet as I focused on getting my work done and meeting the qualifications for graduation. I had no desire to see exactly how failing to complete my program would interact with my state of mind at the time.

With the good graces of what must have been every deity that the human race has ever conceived, I ended up not having to delay my defense date and was able to take the final step in my program at the time scheduled. After an hour and a half of presenting and answering questions, the apex of my academic work up through that point was given a final grade. I had passed.

The relief and joy of successfully defending paled in comparison with the depression that was still hanging over my head. The fact that I’d failed to go on any substantial walk over the two weeks prior was not helping the situation. So as soon as my defense was done and a verdict on my pending educational milestone was reached, I took the bus home, changed into my walking gear, and walked until the sun set and the late night buses were running their last round.

~

There was nothing keeping me in Vancouver once I had completed my degree, so I made the choice to return home for the remaining part of the summer before beginning my job search. My defense had taken place June 22; I needed to move out of my apartment by June 30 to avoid the payment of another month’s rent.

My last walk in the city was a two-block stroll to the corner store to purchase a roll of packing tape. It was such a meager walk that I almost didn’t record it in my notebook, but ended up doing so for completeness’ sake.

Between the time of purchasing my pedometer in November 2010 and leaving Vancouver for good at the end of June 2011, I had walked an accumulated total of 955.67 miles within the city limits. That’s the same number as the number of miles between Jackson, Wyoming and Los Angeles, California. It’s equal to 1,538 kilometers—the same number of kilometers between Paris, France, and Warsaw, Poland. If you were to drive that distance at a steady speed of 60 miles per hour, it would take nearly 16 hours of non-stop driving to do so. It’s the equivalent distance of almost 37 marathons.

My own home town, to which I was returning, was approximately a 430-mile drive from Vancouver—less than half the distance recorded in my walking logs. Upon arriving home, I would find myself living another month and a half beneath the mind-fog of depression before finally feeling it begin to lift organically, without the need for medication.

Addicted to the calmness my mind achieved while I walked, I had continued to do so in my home town. However, it being substantially smaller than the metropolis I’d walked through just months before, there was a certain degree of boredom and of routine that festered quietly in the corner of my mind on every walk. I still wore my pedometer and thus still could gauge the time and distances for my walks, but I did nothing with this information past glancing at the distance reading before resetting it for the next walk. It was distance no longer worth recording.

As for my walking logs from Vancouver, they remain the last bit of proof I have of ever having lived in Canada (now that my bulk-sized Herbal Essence shampoo, purchased at Vancouver’s only Costco, has finally run out) and are the only tangible proof of my walking tour of the city.

I had gotten to know Vancouver the way you get to know a close friend: if you spend enough time in each other’s company, subconsciously observing each other’s habits and mannerisms, you one day realize that they have become a part of your mind and you a part of theirs, like a constant background presence that you find yourself thinking about even when you’re not thinking about anything at all.

Good friends sometimes leave each other with parting gifts when they know they won’t see each other for a long time. I had left Vancouver the rubber soles of my shoes in the form of imperceptibly tiny fragments across the 1.8 million steps I’d taken in the city; she had left me with recorded logs of these steps over the course of the nine months I spent walking her streets.

But we had left each other much more than just these physical reminders. There was a legitimate relationship I’d fostered with the city over the months I’d spent with her as my sole companion. I sometimes feel like I’m losing this relationship as I go about life in the States, the varied memories fading into a hazy cloud that hints at something that used to be more.

Sometimes, when I want to remember just how strong the relationship was, I look to my walking logs as something tangible to trigger something further away—something I cannot quite reach on my own. These logs, a record of my hundreds of trips through Vancouver’s busy streets and thriving neighborhoods, help serve as an element of closeness in a relationship otherwise so strongly defined by distance.

Puh.

This damn English essay, man.

So in sharp contrast to just two days ago, I now have 15 pages of drabble for my Larger World essay in non-fic. Which is cool—that’s the necessary length—except for the fact that I’m probably only a fourth done with what I want to say.

So I don’t know if I should just write all this nonsense out and do some DRAMATIC CUTTING ACTION, or just start over with a smaller scope in mind.

I’ll have to ask my professor tomorrow exactly how long is “too long” for this last assignment. Though he’s already been more than patient with my spazzing over this freaking essay. It seems like the longer I know about an assignment the more I end up botching it.

TOO STRESSED TO BLOG SORRY.

Space Doctor: “Take Two Moons and Call Me in the Morning”

So I’m apparently into self-torture and mental masochism because I’m writing about Vancouver for my long essay.

Part of the reason is because I can’t write in the first place and so my original idea got scrapped.

Another part of the reason is that I’m dumb and can’t think of anything else to write about.

But I think the main reason is because even though I’ve written quite a bit about grad school here on my blog, I’ve yet to really write about my relationship with the city of Vancouver itself. I’ve yet to really write about how my walking routine probably saved my life up there. And I feel like I need to write about those things.

I doubt that a final essay in an intermediate non-fiction class is the place to do so, but hell, I don’t have anything else and this has been pressing against the forefront of my mind for quite some time now.

So that’s that.

In other news: this semester needs to die.

Toasters are Intrinsically Brave

I just hit my 130,000th stumble on StumbleUpon. That translates quite concisely to, “Claudia spends way too much time on the internet.”

In addition, I just found a video of the entire 2010 Winter Olympics opening ceremony.

Rockin’!