The Six Degrees of Leibniz

I submit that on Wikipedia, you can get from the page of any mathematician to Leibniz’ page in 6 clicks or less (even without clicking through the “Mathematician” or “Mathematics” links that show up in like the first sentence of every mathematician’s Wiki page).

Fun Examples for Fun

Starting mathematician: George Polya

Click 1: Probability Theory

Click 2: Probability

Click 3: Christiaan Huygens

Click 4: Gottfried Leibniz

Starting mathematician: George Boole

Click 1: Differential Equation

Click 2: Derivative

Click 3: Gottfried Leibniz

Starting mathematician: John Venn

Click 1: Set Theory

Click 2: Principia Mathematica

Click 3: Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Click 4: Gottfried Leibniz

Starting mathematician: Sewall Wright

Click 1: Philosophy

Click 2: Gottfried Leibniz

Starting mathematician: Henri Poincaré

Click 1: Bernhard Riemann

Click 2: Riemann Integral

Click 3: Integral

Click 4: Gottfried Leibniz

De Moivre!

Today in Complex Variables we learned about the de Moivre formula. So, like I do every time I learn a formula named after some dude, I had to look up the dude to see who he was.

Abraham de Moivre lived from 1667 – 1754 (another one of those long-lived mathematicians) and was friends with Newton, Halley, and Stirling, among others.

Originally from France, he moved to London and, while there, became pretty obsessed with Newton’s newly-published Principia Mathematica and basically memorized the material.

In fact, he took Newton’s binomial theorem and was able to generalize it to the multinomial theorem. This work (plus the fact that he was friends with Newton, I’m sure) got him membership in the Royal Society in 1697.

[And—I have to mention it, I’m sorry—he was one of the dudes on Newton’s little crony committee that was put together to hear the plagiarism charges against Leibniz in 1712.]

De Moivre’s famous formula originated (apparently) from this derivation in 1707:

which he later generalized to this form:

Euler proved it using his own Euler’s formula, so that pretty much cinched it. The reason de Moivre’s formula is so important is because it creates quite a nice connection between complex numbers and trigonometry.

Nifty, eh?

Today is a Blah Factory

Today is the 297th anniversary of Leibniz’ death.

Fittingly, I have had a crap day and don’t feel much like talking.

Sorry.

OH GOODNESS

I AM SO HAPPY

YOU DON’T EVEN KNOW

Edit: AAAAAAAAA SOME OF HIS LETTERS ARE ON THERE! I AM FREAKING OUT WAODIFUALGHALAHGLDGDGHH

Edit 2: BINARY!!!!!

This One is Tumblr’s Fault, I Swear

Someone I follow posted this awesome link to Newton’s notebooks stored in the Cambridge Digital Library (link link link!).

Now that I’ve got access to both Newton’s notes and Leibniz’ notes (thanks to checking out Dr. Wolfram’s awesome post on Leibniz’ archives), you can probably guess how freaking excited I am.

So. Graphology in itself is pretty much pseudoscience, but it’s still interesting to compare the writing styles of these two geniuses, just to see if any similarities/differences stand out. That’s allowed, right? (Screw it, I’m doing it anyway.)

A lot of Newton’s notes were written in English ‘cause…duh…he was an Englishman. From what I’ve read about Leibniz, I think he could read and write in English but not nearly as fluently as in several other languages; most of his work was in Latin, the rest in French and German. So I couldn’t find a good English excerpt from both. So let’s do Latin, just for the sake of keeping the language consistent.

Here’s a Newton page:

Look at his writing, it’s so neat! I’m no handwriting analyst or anything like that, but it looks like this section of Newton’s notes was written slowly and deliberately as if he’s just sitting there going, “yeah, I got this.” There are a few things crossed out, of course, but it looks like he took the time to carefully scratch them out and then just kept going. Slow but steady. And his numbers are so clear, too, holy crap.

The above is just a screenshot of a semi-magnified page; on the actual Cambridge site you can zoom in further and make out the English notes he made in the margin. If you look at a lot of other pages in this section of notes, Newton really seems to keep things very organized, even if it looks like he’s making scratch calculations in some parts.

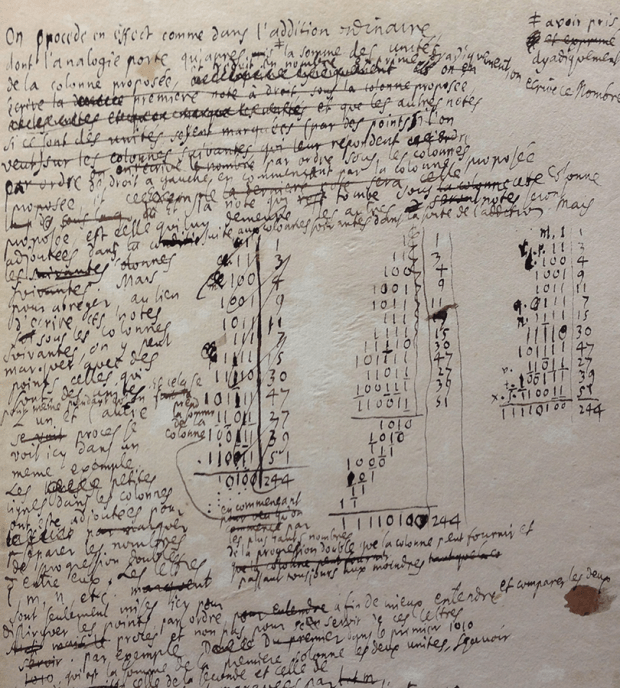

And then there’s Leibniz:

I was planning to do both samples in Latin like I just said above, but I’m snatching pictures of Leibniz’ notes from Dr. Wolfram’s post on him so there aren’t nearly as many choices as with Newton. So I figured a more appropriate comparison would be pages written by both men that contained both words and numbers. I believe Leibniz’ page is written in French, but I seriously can only make out like three words here.

I’m not sure if it’s just because of different writing tools or different ink/paper, but Leibniz looks like he pressed fairly hard (or at least as hard as you could with a quill). Also, in contrast to Newton, it looks to me like Leibniz wrote pretty rapidly. Newton’s corrections were either neat single cross-outs or carefully scribbled out so the mistake couldn’t be read. All of Leibniz’ corrections look like, “no time for error must keep writing!” *scratchscratchscratch* “ONWARD!” Even his numbers look rushed (look, it’s binary!). It almost looks like he used this page for just those calculations but then wrote around them, continuing from a previous page.

On some of the other pages Leibniz really manages to get a lot on a single page. We’re talking ITTY BITTY scrawl, a consequence of his becoming very near-sided in his 20s and it only getting worse as he got older. I’m actually not sure how good (or bad) Newton’s vision was. Of course he did stick a darning needle back behind his eye and wiggled it around (optics experiment), so…

Anyway. Just an interesting thing to see the differences/similarities in their styles.

Green & Stokes

So in my continuing saga of “Let’s Make Stupid Jokes About Everything” (aka, “My Life”) and in the same vein as that Neil & Prey dream I had awhile back, I think someone should propose a detective/mystery show called Green & Stokes. It’d be like NUMB3RS crossed with Law & Order crossed with Columbo, except with exponentially more puns.

They’d work for the LAMD (Los Angeles Math Department) or something, because cities would have their own math departments in whatever universe that would allow Green and Stokes to be mathematicians AND detectives AND live during the same time period.

And the episode names could each be a pun on some other famous mathematician’s name (or other dumb puns).

- “Rolle with the Punches”

- “Out with the Old, in with the Newton”

- “Bourbaki and the Case of the Empty Set”

I DON’T EVEN KNOW.

This is why I need school to start again.

Edit: holy crap, I forgot how crappy gifs can be when they’re exported from Flash (especially when you don’t know what you’re doing), but here’s the theoretical show’s opening animation nonetheless:

Edit 2: fixed it (sort of; it’s still dumb)

Said the statistician with the small sample size to the statistician with the large one: “I’m ‘n’-vious!”

POP QUIZ GO: What Englishman was it that Anders Hall called “a genius who almost single-handedly created the foundations for modern statistical science”?

It’s the same guy who Richard Dawkins labeled “the greatest biologist since Darwin.”

Give up? It’s SIR RONALD FISHER!

An evolutionary biologist, geneticist, and statistician, Fisher lived from 1890 to 1962. He had plans to enter the British Army upon his graduation from the University of Cambridge (where he studied biology/eugenics) in 1912, but he had horrible eyesight and failed the vision test. So what did he do instead? He worked as a statistician for London, among other things. He also started to write for the Eugenic Review, which only increased his interest in stat methods.

In 1918, his paper The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance was published in which he introduced the method of analysis of variance (yup, ANOVA!). A year later, after taking a job with an agricultural station, he began to gather numerous sets of data—both large and small—which allowed him to develop methods of experimental design as well as small sample statistics. Throughout his professional career, he continued to develop ANOVA, promoted ML estimation, described the z-distribution (now used in the form of the F-distribution), and pretty much set up the foundation for the field of population genetics. He also (and I didn’t know this until I read more about him) opposed Bayesian statistics quite vehemently.

Anyway. Thought he deserved a bit of a mention today, since he died on this day in 1962.

Last Leibniz-Centric blog for a while, I promise (maybe)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

This man.

THIS MAN.

Let me tell you about this sexy, badass, wig-adorned genius, shall I?

I just finished Antognazzi’s amazingly thorough biography of him. As I mentioned, I had gotten to when he was 40 years old in the bio by the time I raved about him a few days ago, and so I still had about 30 more years to cover in the latter half of the book.

And let me tell you something: as fascinating as the first 40 years of his life appeared to be, the last 30 were even more amazing.

Here’s the run-down of awesomeness, presented in bullet form so that I can keep track of stuff.

- Leibniz was a very social man. He loved being with people, talking to them about everything and exchanging ideas and thoughts. According to the people in charge of archiving Leibniz’ work/letters/papers, he corresponded with no fewer than 1,100 individuals. That’s insane. And this wasn’t like “Facebook friends approve them and then never speak to them again” correspondence. This was “all his free time was consumed by writing letters to these other people” correspondence. Even when he was older and had bad gout, an injured leg, and was extremely near-sighted, he was still hell bent on getting out of Hanover to visit people. Probably the saddest aspect of this incredibly social demeanor, though, was the fact that he outlived the vast majority of people with whom he corresponded, including many of his closest friends. How sad must it have been for him to slowly lose these people over the course of like a decade (a LOT of them died in the 1690s; Leibniz lived until 1716).

- He. Did. Everything. Far from the “I’ll lock myself in this room and just think for all eternity” picture that I think we tend to have of philosophers, Leibniz was always just out doing stuff. Hell, he personally supervised some of his proposed improvements on the Harz mines (he had some ideas to keep them from flooding) and was constantly trying to start up scientific societies and journals across Germany. Though he appeared to consistently run into bad luck with these schemes throughout his life (money was always tight for him and it seemed like every time he got a project going there’d be one thing that’d go wrong and cause everything to fall apart), he never let go of many of his main projects aimed at improving the world.

- For all his running around in mainland Europe, he was not one to shirk (at least entirely) the duties set forth to him by his various employers. Example: his main employer in his later years, Georg Ludwig, put him in charge of writing a complete history of the House of Guelph (a dynasty of German and English monarchs). This was supposed to take like 10 years max but, Leibniz being Leibniz, he kept the task in the back of his mind as he traveled about and slowly began to amass a huge amount of information he deemed relevant to the history. Ludwig was always asking him, “Hey man, how’s that history comin’?” and Leibniz always managed to say, truthfully, that he was still researching, all the while sneakily making his way around the continent to do the other Leibniz things that he really wanted to focus on. However, as time went on and Leibniz continued to travel much to the dismay of his employer, tension rose between the two and Ludwig became more and more upset with him. I particularly enjoyed this little quote of frustration: “at the very least he [Leibniz] should tell me where he is going when he takes off. I never know where to find him.” By the time Ludwig was finally like, “Gottfried, dude, just sit your butt down and write this thing or I’m suspending your salary!” the amount of material Leibniz had gathered was so extensive that the history actually was left unfinished by the time he died. And that’s even with him spending the last 5 years or so of his life sequestered in his study (he was pretty much forbidden to travel by that point), frantically trying to get it done so that he could pursue more important tasks.

- I mentioned this before but it bears mentioning again, because it’s one of the main reasons I like Leibniz so much: it seems like he was a good guy. The idea a lot of people seem to have about European White Guys, especially of that era, is probably something along the lines of, “each one thought they themselves were correct in their thoughts, ideas, and philosophies, and all other cultures/genders/backgrounds/European White Guys were unquestionably wrong!” Leibniz communicated with men, women, uneducated people, very learned people, people from many different countries…and from what it sounds like, he was just very open to the possibility of views different than his own. He seemed to take it all in and use it—regardless of who/where it came from—to further refine what he himself believed or knew. He was also a major Sinophile, in part because of his interest in creating a “universal alphabet” and the parallels he saw between that and Chinese symbols/writing.

- Even when people disagreed with him he seemed to retain a polite congeniality in correspondence with the disagreeing party(ies). The one exception to this appears to be the final years (at least for him) of the calculus dispute. But by then he was really just like, “gettin’ real tired of your shit, Keill,” which honestly was quite a valid reaction by that point in time. (Side note: I really like how this biography talks about the calculus dispute but doesn’t make it the focus of Leibniz’ last few years of life. It really emphasizes that even though he was at war with freaking Isaac Newton and his cronies, he was still trying to bring his other more important projects to fruition).

Just…nnnf. I love this guy.

Man, I was going to restart my fiction list today with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, but I don’t think I can read anything else for a few days. I’m like in mourning now that I’ve finished this book. I seriously recommend reading it, even if you’re not a hardcore Leibniz fangirl/fanguy/whatev.

Happy Birthday, Leibniz, You Magnificent Human Being

OH YOU KNEW IT WAS COMING.

LEIBNIZ DAY!

367 years ago today, the coolest polymath to ever exist was born.

I was hoping to be through Antognazza’s biography of him by today so I could extoll every inch of his beautiful mind that is covered in the 664-page bio, but alas, calc III happened (not that I’m complaining) and so my reading time was severely hindered. So I’m about halfway through as of writing this blog (I think he’s in his 40s at this point in the bio).

And with each page I’m like, “holy monads, Batman, it is not possible to like this man any more than I already do.”

And then I read the next page and I like him even more.

It’s hard for me to express exactly why I like Leibniz so much. As I mentioned in a past blog, as soon as I started reading his work and reading about him in general I felt this weird connection with him. Like we were supposed to know each other but the universe was like “NOPE!” and threw us into the mix a couple centuries apart.

(Don’t judge me, I’m really trying to not sound creepy. Am I failing miserably?)

And as I’ve mentioned in other blogs, it really seems like he was just a good guy. He wasn’t a buttface to those who disagreed with his philosophy or ideas about the natural world. He was accused like five separate times of stealing others’ ideas (which he never did) but never totally flipped out and started smothering people with his wig. According to the reports of his contemporaries, he was very kind, congenial, and graceful in social settings. The ladies seemed to dig him (SMART LADIES!). AND he was about as naturally intellectually curious as a person could be.

Seriously. A year after his father’s death when Leibniz was six, he inherited his library and immediately worked to teach himself Greek and Latin so that he could read the works of the ancient philosophers (his father taught moral philosophy at the University of Leipzig). He received his law degree when he was like 19 and for his doctoral dissertation he wrote some work on permutations/combinations that was fairly groundbreaking. And this was before he even started to seriously get into the field of mathematics.

Yup, the guy who invented calculus didn’t really start into math until his twenties. He was interested in law and philosophy originally, but as he continued to refine his ideas he began to move into math. As he began his travels around Europe after finishing his education, it became clear to him that his mathematical knowledge was lacking. So he was like, “oh crap, better catch up!” and pretty much taught himself everything without anyone’s help

Actually, when I was reading about his early life in the bio, it was this fact that he was so self-taught that was really the cause behind most of the accusations of plagiarism he faced. He didn’t start out in math, as I said, so he had to catch himself up. Along the way, he started making advancements and discoveries that, to him, were new and unique, and thus he eagerly published them. But unbeknownst to him, several of these major discoveries were things that had actually been discovered and published not too long before. So some people (*cough*Hooke*cough*) were like “hey, you totally got that from [insert mathematician here]! THIEF!” even though he had come up with it on his own.

Really. That happened to him like three times even before the whole calculus thing.

And did you know he was the one who came up with what is today known as Cramer’s Rule? Truth! But like a lot of the stuff he developed, it was so advanced for his time that it just kind of sat in his notes and wasn’t used for a long time.

(Like his binary!)

But I think the one thing that I really, really like about him is the fact that he was always looking for connections between everything. He was convinced that even the most isolated bits of the universe and of human knowledge were connected to everything else and that a system could be developed with which we could express these connections and better understand them. In everything he did, he always seemed to be driving towards defining this system and better describing the connectivity of the universe.

And that’s just cool.

NNNNNNNNNNNNF I JUST LOVE HIM, OKAY?

(I live in a fantasy world where Leibniz and I are married and he does calculus and I do statistics and we do each other and life is perfect.)

Um…anyway.

Expect another Leibniz-heavy blog when I finish the whole bio, ‘cause it’s going to happen whether you like it or not.

Until next year!

Happy birthday, Gottfried! <3

OH CRAP SORRY PASCAL

So I hadn’t checked my little mathematician birthdays database in awhile and decided to check it yesterday. It turns out I missed Pascal’s birthday by a day. He was going to get my blog yesterday but I was distracted by freaking out about my final. I’m still freaking out about my final, but I have nothing else to blog about related to it. So Pascal shall get my blog today instead!

Though he only lived the 39 years between 1623 and 1662, Blaise Pascal was an incredibly accomplished mathematician and inventor. He was educated by his father and was still in his teens when he began to explore advanced topics on his own.

He was interested in math (particularly geometry) early on; when he was 16 he wrote an essay on conic sections that was so advanced that Descartes read it and thought that Pascal’s father had actually written it for him.

Little Pascal was also very interested in the idea of a mechanical calculator, and he was strongly motivated to produce the first working prototype of what was called the “Pascaline” in 1642 to help ease his father’s work as tax commissioner for the king of France. The calculator could do addition and subtraction* and was a great help to his father, but because of its cost it failed to be a commercial success.

Probably Pascal’s most famous contribution to mathematics is Pascal’s Triangle and the closely-related Pascal’s rule which states how the triangle is to be constructed. The triangle displays the binomial coefficients resulting from the binomial theorem along with other really cool properties (might have to do a blog just on his triangle here in a bit…). The development of this triangle led to conversations with Fermat, and the two collaborated together to develop probability theory.

In addition to his contributions to math, Pascal also gave the world the hydraulic press, the syringe, and did a whole ton of experiments with vacuums and hydrodynamics (he’s got the SI unit of pressure named after him as well, though that obviously happened much later). Some of his most famous demonstrations of the effect of elevation on atmospheric pressure involved carrying barometers to the tops of churches to see what happened to the mercury levels.

Cool dude, huh? See? 17th-century Europe!!

BLOG COMPLETE!

*The Pascaline was what Leibniz was trying to improve on with his Step Reckoner by including also the functions of multiplication and division.**

**Yes, I have to mention him in every post.

Goin’ Green

I’M DOING IT AGAIN!

Today we learned about Green’s Theorem. So who is this Green fellow?

[Edit: Okay, originally I was just going to talk about Green ‘cause while Green’s Theorem is just a special case of Stokes’ Theorem, we haven’t learned the latter yet. But turns out both Green and Stokes are named George and that’s hilarious, so we must press on and speak of both.]

So who are these two fellows?

George Green lived from 1793 – 1841. Like what seems to be a large proportion of mathematicians at the time, he was British. He lived in Nottingham. There are two reasons why these are interesting facts:

1. Nottingham, at the time, wasn’t really burning it up intellectually. Only about 25-50% of children received any sort of education, and Greene himself attended an academy for only one year when he was 8. It took him until age 36 to gather enough money (and free time) to afford a higher education (and he died when he was 47, so unfortunately he didn’t have too much time to enjoy it).

2. Despite the setbacks as far as formal education goes, Green was a very smart dude. He was largely self-taught (obviously) and once he finally got to Cambridge he pretty much kicked ass. What’s most interesting, though, are his studies in math. Historians aren’t exactly sure how Green reached the understanding of calculus that was necessary for developing his theorem. He likely used the “Mathematical Analysis,” which was a form of calculus Leibniz developed, but this was during the post Newton-Leibniz controversy over calculus and England pretty much forbade the use of everything calculus-related that originated from Leibniz. ‘Cause they had Newton’s calculus. Never mind that Newton’s notation was inferior and didn’t lend itself to the applications/developments that Leibniz’ notation did and that forbidding the better notation/methods from the England set the country back in mathematical advancements for like a century.* But somehow Green got a hold of it and made his improvements and came up with his theorem and was generally awesome. (LEIBNIZ POWER! Okay, I’m done).

And what about George Stokes? Who was he? Stokes’ life overlapped the end of Green’s life (1819 – 1903). Stokes was Irish and rocked the fields of fluid dynamics, optics, and mathematical physics. He actually did quite a variety of things, so I’m just going to list a few.

- He came up with a way to calculate the terminal velocity of a sphere falling in a viscous fluid (Stokes’ Law!)

- He expressed a mathematical description of rainbows using a divergent series, something that wasn’t really understood just yet by most.

- He was secretary and then president of the Royal Society.

- He wrote a paper in which he tried to describe the variation in gravity across the earth’s surface.

- And, of course, Stokes’ Theorem in math.

YAY GEORGES!

Sorry, I’m going to keep doing these little mathematician snippets until…well, until I feel like stopping. So ha.

*I’m not bitter.

Shoutout to Newton

Let’s clear up a misconception today.

Despite how much I bitch about him, I do not dislike Sir Isaac Newton.

I don’t know how anyone really could dislike the guy. I mean come on. Anyone who can contribute that much to science and society deserves the utmost respect, even if he wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with. Personality does not beget worth—it’s what you do that counts.

Anyway.

He actually is one of my favorite scientists, and it baffles me just how much he did. It’s really incredible. I would have liked to know him. I just bitch about him a lot because of the whole calculus thing, ‘cause my main man Leibniz got screwed over and that makes me want to invent a time machine so that I could go back and maek things right and then make out with him for the rest of eternity upsets me.

But I do not dislike Sir Isaac Newton.

So shoutout to England’s greatest scientist! I’d make a horrible pun here in your honor, but I can’t think of any right now.

Claudia’s Alternate History Party

GUYSGUYSGUYSGUYSGUYS I’m hyper.

You know what I would love to do (even though it would screw history and the rest of existence up because that’s how these things work)? I would love to take a graphing calculator and a calculus textbook, go back in time, and show them to Leibniz.

“Look!” I’d say. “See this little itty bitty machine? Look at all this nonsense it can do! Not only can I add, subtract, multiply, and divide in a fraction of a second, I can also find square roots, sines, cosines, and tangents, and GRAPH FUNCTIONS! This is your Step Reckoner on steroids. YOU helped pioneer this! EVERYBODY uses these now.

“And look at this textbook. This is what we use to teach calculus to people today. Let me show you some of these symbols. See what we’re using? dy/dx! And the elongated S! We’re still using YOUR symbols because they remain the clearest, easiest, most adaptable ones for this branch of math. AND THIS COMING FROM THE FAR-OFF YEAR OF 2013!!”

Ignoring the whole “somebody just time-traveled!” aspect, I think the calculator would really be the thing that would blow his mind. I mean, the Step Reckoner was massive and it just did the four basic operations. Plus, you know, the fact that the calculator now has this crazy-ass digital display thing. I’d totally help him take it apart and do the best I could explaining what the components were.

Of course I’d probably end up having to lean in reeeeeeeally close to him to do that.

Y’know.

OH DEAR LORD

ASDFLKADFAGLADKFADSDFSGG I NEED TO GO TO HANOVER LIKE NOW

Like, I knew a lot of Leibniz’ work was archived, but I didn’t know there was so much.

(If you could’ve seen me reading this article, I was like a 12-year-old Belieber flipping out right in front of Justin on stage).

Look at this beautiful man’s beautiful handwriting. LOOK AT IT.

INTEGRAL SYMBOLS IN THEIR NATURAL HABITAT *flailing*

I just…I need to go there.

*all pictures from Stephen Wolfram’s blog, linked above*

ZOMG KLEIN AND KOLMOGOROV

(Again, sorry for spamming y’all with mathematicians.)

(Also, I’m using this as a distraction from the fact that I’m a complete moron who will never amount to anything ever.)

HOKAY.

SO.

Two badass math fellows were born on this day.

1. Felix Klein (isn’t that a badass name?)

Klein was a German mathematician born on this day in 1849. He is most famous for the non-orientable surface named after him: The Klein bottle!

Picture (from Wiki):

A Klein bottle is similar to a Mobius strip except unlike the Mobius, it is a closed manifold rather than an open one. And while a Mobius strip can be imbedded in 3-D space (which is why we can make them with just a piece of paper and some tape!), a Klein bottle cannot.*

2. Andrey Kolmogorov

Kolmogorov, a Soviet mathematician born on this day in 1903, was known for quite a lot of things, but for me the thing that jumps out is the nonparametric statistical test he had a hand in developing.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is one used when your data just aren’t being normal but you still need to examine them somehow. In particular, the test is used when you want to determine if two datasets differ significantly. It gets around the issue of nonparametric-ness by making no assumption about the distribution of data in either set.

I’d go into how, but it’s late and I have to get up early tomorrow and if I start talking about stats I won’t shut up for days, so make me promise I’ll do a blog on the K-S test later.

But yeah. Two awesome math dudes today! Woo!

*That doesn’t stop people from making Klein-esque models. If you want a Klein bottle model, go here.

N-N-N-NAPIER

I should just change my (semi-)weekly science blogs to “In This Blog Claudia Blah Blahs about a Mathematician” because that’s pretty much what I do weekly anyway.

(It’s ‘cause of that damn birthdays site, man.)

Today’s feature: John Napier of Scotland!

Yeah, he was a cool dude. Did some stuff, you know, just a few small things like DISCOVERING LOGARITHMS.

Napier studied math as a hobby (his main focus was theology) but, wisely, turned more towards math upon discovering logarithms and subsequently publishing a book about them in 1614. He created tons of calculating tables that were used to make calculations involving e much easier. He also invented an abacus-like device that could be used to quickly calculate products and quotients of numbers. This tool was called Napier’s bones because it involved the use of 10 long rods printed with numbers. The rods, back in the day, were made of ivory and thus looked like long bones.

He also did work with decimal notation, refining previous notational standards set in place by Simon Stevin.

Despite natural logs being my natural enemy (HA GET IT no seriously my brain cannot handle them), I’ve gotta admit that discovering freaking logarithms is pretty damn snazzy.

Not “discovering calculus” snazzy, but snazzy nonetheless.

END!

N-N-N-NAPIER

EeEEeeeEEEEEeeeeeeee

Happy birthday, Pierre-Simon Laplace!

Considered the “Newton of France”, Laplace is another one of those guys who just did EVERYTHING. He did a lot with probability—both Frequentist and Bayesian—and he’s even got a distribution named after him.

Anyway.

I know at least three of my readers dig The Oatmeal. Today I read a comic of his that I’d never seen before. I advise you to read it as well if you haven’t yet come across it.

Who is this Taylor guy, anyway?

We’ve started Taylor series in calc this week. Which is cool; I think I’m understanding what they are/how they work/why they’re important. But one thing I don’t know is who this Taylor fellow is.*

TO THE WIKIPEDIA-MOBILE!

So it looks like Brook Taylor was an early 18th century British mathematician. He did some work on the then newly described calculus, coming up with work Lagrange popularized in the late 1700s and, of course, came up with Taylor’s Theorem and Taylor series.

Here’s a cool demonstration of Taylor series approximation for various trig functions.

Edit: OH GODS HE STUDIED UNDER KEILL. Why, Taylor, whyyyyy?!

Edit 2: he was on the Royal Society committee set to hear Newton’s claims against Leibniz, too! Whaaaaat.

*I wish more teachers gave at least brief little intros on the people who come up with all this cool stuff. Especially when we’re learning about something expressly NAMED after someone.

LEIBNIZ.

Have I mentioned lately how much I love this man?

(Yes you have, Claudia. Shut up.)

(NEVER!)

The more I read about him the more I like him. And I’ve read a lot about him, so I like him a lot.

I mean, not only was he a freaking genius with the wig of a god, but he had to deal twice—twice—with being publically accused of stealing the idea of calculus from Newton. First from Fatio, who Newton actually quelled when Leibniz wrote him and said, “hey man, this dude’s saying false things about me!”

And did Leibniz set out to ruin Fatio the way Fatio was wanting to ruin him?

Nope!

He was like, “I won’t stoop to that level. I’ve got more important things to do with my time.”

And then there was Keill. And Keill was out for blood, man. He publically and without reservation bellowed claims of plagiarism to all who would listen.

And once the accusations actually reached Leibniz I’m sure he was like, “ugh, not this again.” But even after all that insanity, Leibniz did very little to Keill. He still tried to maintain his “I’m above all this nonsense” even after Newton’s Commercium Epistolecum was published, totally slandering his name.

He just seems like he was a good guy. That makes me happy.

Now back to obsessively stalking dead people!

More birthday stuff

I can’t stay away from that website with the mathematician birthday/deathday data.

So I decided to look at the data a little differently this time. Each square represents either a death or a birth on the day of the year. The data are broken up by month by a small white space.

Note the “most eventful” and “least eventful” days. And look at October and all its within-group variance.

I think I’m going to do some stats on this data. Because that’s what I do. But I can’t do it for like another week, since next week involves LOTS of studying/homework/panic attacks.

BUT LATER!

More birthday fun!

This is fantastic info right here.

I don’t know why, but birthdays and the distribution of birthdays is really fascinating to me. I’m going to have to analyze this somehow.

And the birth and death statistics page is awesome, too. Interesting, interesting stuff.

Edit: compiled ‘em!

It’s kind of cool that I found this today, as today was the birthday of Rene Descartes! Happy birthday, Rene!

Edit 2: Not only did we lose l’Hopital on my birthday, but we lost Bertrand Russell as well? Man, throw in the birth of Ayn Rand* and February 2nd has not been kind to the world.

*James Joyce’s birth almost makes up for this.

In Honor of Newton’s Birthday*

Anybody who knows me at all knows that I get really, really obsessive about things. I kind of go off on these monomaniacal mental benders where whatever it is I’m obsessing over is doggedly demanding as much of my attention as it can get.

If you’ve perused the last month’s worth of posts here, you know that the current item of obsession is the calculus priority dispute. Obviously the Leibniz factor plays a big part as to why I’m so into this particular bit of mathematical history, but there’s another component that’s equally as fascinating to me.

The reason I went into psychology when I first started college was really because of my interest in intelligence. The various ways we measure intelligence interested me and I was curious as to whether there could be alternate scales produced that would better get at whatever latent factor(s) composed what we call intelligence.

Along those lines, the idea of “genius” has always been intriguing to me as well. I sit here and read about these ridiculously ingenious dudes and I cannot imagine what it would be like going through life with a mind of that caliber. What kind of unique thought processes must you have in order to theorize and describe universal gravitation? How must have Newton seen the world and interpreted even the most mundane of things? Did Leibniz go through life examining every facet of his experiences trying to see how to fit everything into his attempt to create an alphabet of human thought? What kind of mind does it take to go from “I feel that my mathematics knowledge is inadequate” *studystudystudy* “oh, here’s this new thing I came up with called ‘calculus’!”?

I’m such a pleb I can’t even fathom the depth of thought these guys (and other ridiculously intelligent people like them) possessed. It would be the coolest thing to be able to experience that level of understanding, even for like five minutes.

And then, of course, you have to wonder what that component (or components) is (are) that pushes someone from “normal intelligence” to this level of genius. And that brings up the question of whether we all possess that level of thought and the only thing separating “regular” people from the super geniuses is some other component of brain chemistry/personality/persistence/something else.

This is something I’m pretty much always thinking about; the whole calculus thing has just brought it back to the forefront of my mind.

Anyway.

Oh, and Merry Christmas, y’all!

*Newton was born before the English switched to the Gregorian calendar (they were using the Julian calender back when he was born); using the Gregorian puts his DoB on a different day.