Stats from the Past

While digging through the book bin at the recycling center, I came across this awesome find:

It’s a stats book from 1951!

It was really interesting looking through this, ‘cause this book was published way before SPSS, SAS, R, or any other software (at least, any other stats-centric software) was readily available.

Thus, we get examples in which all the calculations are done using the formulas rather than being read from an output table. Here’s some regression:

And t-scores:

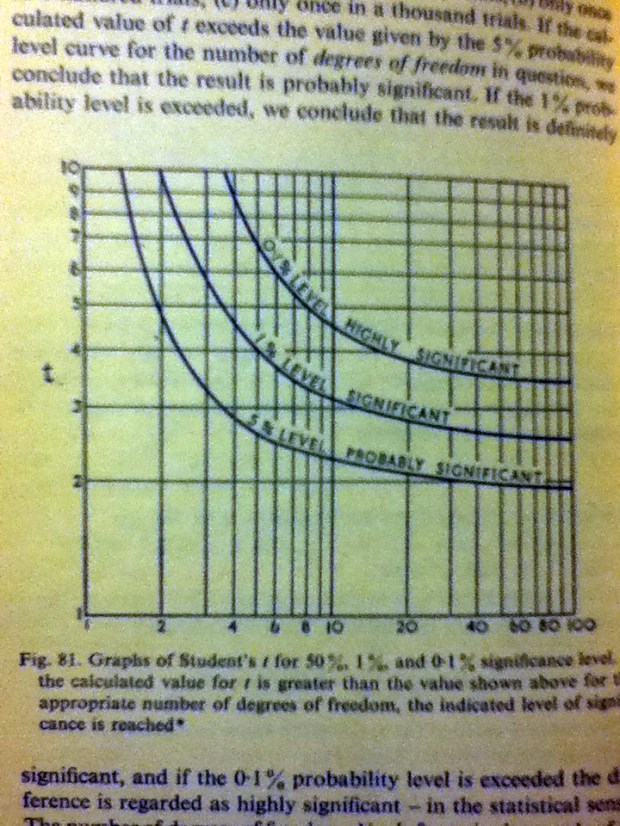

And of course the t-table (in graphical format):

I didn’t even teach how to read a t-table in STAT 251. It was mainly because we just didn’t have time to do so, but considering we have ALL THE SOFTWARE today and, for all practical purposes, that’s what people use in “real life” nowadays, I focused instead on how to read output (and how to appropriately interpret it, of course!). I did have a separate sheet on how to understand a t-table that students could check out on their own if they wanted.

I’d show you pics of the ANOVA calculations, but there are a lot of them, haha.

DONE!

THE SLOPE! THE SLOPE! THE SLOPE IS ON FIRE!

(Yeah, I’ve pretty much given up on my titles.)

So here’s a question that you may or may not have pondered: when we write the slope-intercept equation for a line, the m in y= mx + b is our slope, right?

Why the heck do we denote it with “m”?

There’s quite a range of theories.

According to Pat from Pats’blog, the word “slope” itself is derived from the Latin root slupan for “slip.” Which makes sense when you think of what the slope actually is.

A common myth is that Descartes first used m because it was the first letter of some French word related to slope, but according to a bunch of people who speak French (and we should probably trust them about their language) the appropriate word for slope is “pente.”

Pat digs up some info from Jeff Miller, who claims that the earliest use of m dates back to 1844 when Brit Matthew O’Brien wrote “A Treatise on Plane Co-Ordinate Geometry” and Irish George Salmon published “A Treatise on Conic Sections.”

Another possibility was pointed out by John Conway, who suggested that m could stand for “modulus of slope.”

But in the end, no one’s really sure exactly when and why we got to using m for slope. I’m sure there are a fair number of mathematical symbols we use that don’t have a clear origin, but I know I’ve never really thought about m for slope before. I guess that’s because when I first learned y = mx + b I always thought m was appropriate because if you follow the trace of the letter the slope changes a whole bunch.

I was a dumb kid.