“How Long Have You Been Waiting for the Bus?” IT DOESN’T MATTER!

Today I’m going to talk about probability!

YAY!

Suppose you just went grocery shopping and are waiting at the bus stop to catch the bus back home. It’s Moscow and it’s November, so you’re probably cold, and you’re wondering to yourself what the probability is that you’ll have to wait more than, say, two more minutes for the bus to arrive.

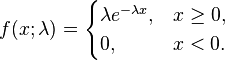

How do we figure this out? Well, the first thing we need to know is that things like wait time are usually modeled as exponential random variables. Exponential random variables have the following pdf:

where lambda is what’s usually called the “rate parameter” (which gives us info on how “spread out” the corresponding exponential distribution is, but that’s not too important here). So let’s say that for our bus example, lambda is, hmm…1/2.

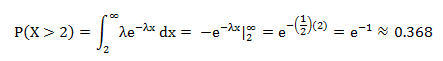

Now we can figure out the probability that you’ll be waiting more than two minutes for the bus. Let’s integrate that pdf!

So you have a probability of .368 of waiting more than two minutes for the bus.

Cool, huh? BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE!

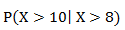

Now let’s say you’ve waited at the bus stop for eight whole minutes. You’re bored and you like probability, so you think, “what’s the probability, given that I’ve been standing here for eight minutes now, that I’ll have to wait at least 10 minutes total?”

In other words, given that the wait time thus far has been eight minutes, what is the probability that the total wait time will be at least 10 minutes?

We can represent that conditional probability like this:

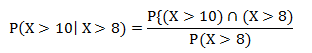

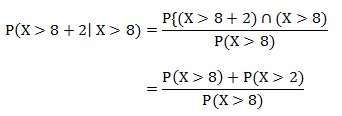

And this can be found as follows:

Which can be rewritten as:

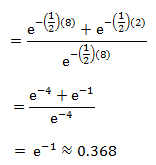

Which is, using the same equation and integration as above:

Which is the exact same probability as the probability of having to wait more than two minutes (as calculated above)!

WOAH, MIND BLOWN, RIGHT?!

This is a demonstration of a particular property of the exponential distribution: that of memorylessness. That is, if we select an arbitrary point s along an exponential distribution, the probability of observing any value greater than that s value is exactly the same as it would be if we didn’t even bother selecting the s. In other words, the distribution of the remaining function does not depend on s.

Another way to think about it: suppose I have an alarm clock that will go off after a time X (with some rate parameter lambda). If we consider X as the “lifetime” of the alarm, it doesn’t matter if I remember when I started the clock or not. If I go away and come back to observe the alarm hasn’t gone off, I can “forget” about the time I was away and still know that the distribution of the lifetime X is still the same as it was when I actually did set the clock, and will be the same distribution at any time I return to the clock (assuming it hasn’t gone off yet).

Isn’t that just the coolest freaking thing?! This totally made my week.